Reviews

Read below for details of publication dates, text and photographs.

POET-SEERS WITH A TOUCH OF THE PROPHET

A review of 'Bob Dylan & William Shakespeare: The true performing of it' by Andrew Muir

Isis

Issue 203

August 2019

pages 21-24

“Art is the perpetual motion of illusion.”

— Bob Dylan, December 1977

Jonathan Cott interview, Los Angeles, California.

Overview:

I begin this review with the transparent confession that I was one of Andrew Muir’s draft readers for his latest book, Bob Dylan and William Shakespeare: The true performing of it. I was fortunate enough to watch as it took shape, and to have a small role in the process. However, like watching the construction of fine pottery or complex wood turning, it wasn’t until I held the finished product in my hand - glazed and fired, sanded and polished, printed and bound - that I was able to truly appreciate what has been created.

The book is written in Muir’s trademark style. As with his previous books and articles, he approaches his subjects with directness, clarity and sharp focus. His writing has a depth of understanding and obvious enthusiasm that allows him to address each aspect with a level of passion, warmth, and accessibility. In addition, this text brings something extra. In dealing with the works of the most celebrated writer in the English language, Muir tackles the Shakespearean content with a commendable level of academic rigour and research. He uses interesting sources well, draws clean correlations, and executes an even balance between discussion of Dylan and Shakespeare.

Before diving into an appraisal of the contents of the book, I think it is important to recognise the validity of writing a comparative study placing Bob Dylan and William Shakespeare within the same literary space.

Comparative studies emphasise that we are part of the human continuum, and highlight the cultural heritage wending its way through popular art and literature. It is through historical and cultural comparison that we can measure the growth of human civilisation - and also see where we have stood still. Culturally, we can best understand the nature of humanity by studying a comparison of intertwined human history in terms of literature, language and art. It is the evolutionary branch of the ‘tree with roots,’ where some stems are shared whilst others branch off into new clusters of leaves and blossoms, producing the seeds from which the next generations will grow.

However, it must be made clear that, as Andrew Muir points out in his recent interview with Derek Barker, this book is not a direct comparison of Bob Dylan and William Shakespeare. It gathers common themes and similarities, connections and parallels, discusses their working practices, and examines both artists by considering how they express their ideas. The book in no way ‘ranks’ the two or seeks to place Bob Dylan as a peer with, or equal to, Shakespeare. Here in Andrew Muir’s book, we have the convergence of popular art and academic study that focuses on the similarities between Bob Dylan and William Shakespeare; and by comparing the two he allows us to consider each in a new light. An initial overview of the book shows that it is well-structured and clear in purpose. Topics are well-organised and relevant, and longer chapters are made easier to digest by the use of carefully placed subtitles that are both playful and useful. Muir uses quotations and examples from a variety of writers, commentators, dramatists, musicians, actors, and poets from different eras and genres. A pertinent and enlightening use of quotations shows the depth and timeless relevance of both Dylan and Shakespeare. This gives the book an expansive feel that widens the discussion and includes ideas that bring fresh insight to two artists that have already been written about so frequently, it would seem an impossible task to introduce a new perspective.

And yet, this is what I feel Andrew Muir has successfully done.

Introduction to the bards:

Muir eases us into the content through a clear explanatory introduction and then by delving into the definition of the term ‘bard’. For, as Muir states, “Bards encompass all of life in their work and give a voice to everyone in society.” Bards are not just geniuses who sit on a pedestal showering wit and wisdom upon the masses - they are from the masses. One of us. Speaking the thoughts and feelings that we ourselves cannot put into words or song.

There is an interesting quotation from Seamus Heaney about that third ‘bard’ Robert Burns, considering how language in common usage changes and dies, but can live on in the words of poets, playwrights and balladeers. It is a thoughtful discussion of how a poet’s language can influence everyday speech and language. This is an important element as the symbiotic relationship of language and culture is undeniable. Language always carries meanings beyond itself, words can have alternate definitions in different situations. Grammar rules change; and linguistic frameworks can denote everything from social position, age, gender, geographical location and economic class. It is a blurred line, and one a bard knowingly crosses with purpose, rewriting the rules, creating new forms of expression.

Muir’s own use of language here (and throughout the book) is rich, strong, and descriptive. From the perdurable nature of Shakespeare’s popularity and the polyphonic universality of bards, to the alliterative roll and bounce when describing how our protagonists’ works range from the ‘sordid to the sublime’, the ‘earthy to the divine’ and how the idyll of nature was a myth hiding ‘dirt, death and a plethora of unpleasantries’. Each paragraph is carefully composed to ebb and flow and echo the subject matter.

There is, of course, an elephant in the room - one that is addressed early on by Muir. Ever since being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016, there has been a recurring question mark hanging over the validity of Bob Dylan being worthy of such an honour. But as Muir rightly points out, beyond the committee awarding the prize to Dylan for “having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition,” the modern-day bard did so much more - literally exploding the form of popular song and poetic structure.

The true performing of it:

In discussing the importance of performance, there is indeed a correlation between Shakespeare writing plays to be acted, and Dylan writing songs to be sung live. Art is evolutionary, and Muir provides an intriguing look at the fluidity of the writing process for those whose work is performance-based. The audience reaction, the atmosphere affecting how work is received, and the nebulous nature of collaboration affects the process of editing and leads to the ensuing multiplicity of texts. Creation is evolutionary. Of particular interest to some readers will be the battle between maintaining artistic integrity whilst still aiming for commercial popularity. The romantic mythology of the ‘starving artist’ retaining their creative principles in the face of commercial necessity is just that - a good story; but one that ultimately does not always hold true, as embodied by such writers as Dickens and Dostoyevsky. However, one genuine conflict can be the discord between what an artist wants to perform and what an audience wants to see and hear.

An interesting connection is that during Shakespeare’s time, theatre was considered to be the lowbrow entertainment or the masses and was not really taken seriously as ‘high art.’ The writers of plays would often work collaboratively and not have their names listed as author. Of course, although authorship (and copyright) is now considered as a horse of a different colour, pop and rock music is today considered ‘low art’ and lowbrow entertainment for the masses. Muir emphasises, amongst many other salient points, that Robert Louis Stevenson thought Robert Burns was wasting his time writing lyrics for folk music rather than focusing on ‘serious’ poetry. Similarly, when the book explains how John Lennon emphasised that the sound of Bob Dylan’s music was more important than the lyrics, I felt Lennon had demeaned the actual power of what Dylan has to say. Because Dylan’s lyrics are complex, contradictory and inter-connected with the music and vocal performance. Dylan uses literary sources, structuring the songs linguistically, and including the strength of his delivery to convey nuanced meaning.

And that is the crux of the entire book for me - the nature of performance - as noted from the start in the title itself.

In watching the recent Martin Scorsese film about Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue, Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story, I was intrigued to see how many connections there are to this book within the film - and it all centres around performance. Within Shakespeare much is made of the use of disguise, deception, the farcical nature of mistaken identity, the confusion of gender identity, the blend of comedy and tragedy. During his time, members of the audience attending Shakespeare’s plays would also disguise themselves so as not to be associated with entertainment that was beneath their status. Consider the parallel between this and Bob Dylan’s use of masks, the movie Renaldo and Clara where it feels as though nobody is their true selves, where people switch identity, where Joan Baez dresses as Dylan and is mistaken for him by members of the crew until she speaks. The Scorsese movie uses a clip from Wladyslaw Theodor Benda’s ‘The Terrifying Mask Man’ (1932), and there is a ‘Pinocchio Paradox’ in Bob Dylan using the Oscar Wilde aphorism, “Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.” Dylan states this whilst not wearing a mask. Or is his persona a permanent mask? In the Shakespearean tradition of a ‘play within a play,’ there is a case to be made for the artists revealing fundamental human truths through fiction.

Wordplay:

Muir’s chapter on wordplay is a delight for those of us interested in the role of paradox, punning and hendiadys in expressing the contradictions and (sometimes dark) humour of the human condition. Both Dylan and Shakespeare make effective use of varied forms of wordplay, creating concepts that are contradictory yet interrelated; statements of valid reasoning from true premises that lead to logically absurd conclusions but still somehow maintain a truth. We know about Shakespeare’s specific comedies (and Muir explores the sometimes spurious classification of Shakespeare’s plays with an acceptable level of cross-examination), and it is good to be reminded of just how downright hilarious and riotous Bob Dylan can be - in more ways than one.

In quoting Charles Moseley on William Shakespeare, Muir points out how speech (including the way we use and understand wordplay) is both a part of identity and also can create identity. Language ‘shapes the reality the individual inhabits’ and, I would argue, vice versa.

My previous article ("Beyond an angel's art: Bob Dylan's voice, his vocal styles, delivery, and the oral tradition of storytelling through song." ISIS 193, August, 2017) referred in detail to how Bob Dylan uses language, linguistic and vocal techniques, and prosody to portray a multitude of protagonists, and a multitude of ever-shifting emotions, in his songs. The selection of words, the use of puns, emphasis, vocal tics, cadence, and the incredibly skilful use of pauses and comic timing, shapes the character and atmosphere of performance.

More than humour, though, wordplay is wit: a socially intelligent, shared, subtle language that allows communication between the performer and audience about subjects that might otherwise be difficult, vulgar, or taboo (such as sex, death, mental illness, fear, or drug use for example). It may also be a way to connect in a language style that would be entertaining, amusing, memorable, and meaningful to an ‘in-group.’

Opposition and religion:

Muir dedicates two chapters (separately) to ‘Opposition’ and ‘Religion’. I write here of the two sections together, because whilst each are interesting themes, by comparison and confluence we really begin to see the social and cultural threads running through the works, as well as the congruity of the reception faced by both Shakespeare and Dylan across their respective societies. The discussion of how the religious content manifests itself with each artist is a rich seam to explore, Biblical references and glorious imagery abound and the themes of both artists reflect the religious and social concerns of their times - death, violence, contemplation of the value of life, morality... Elizabethan concerns are echoed by the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Rock ‘n’ roll music and Shakespeare’s plays were considered wicked, lewd, slanderous and a source of evil by sectors of their societies. The burning of music records seems like a disproportionate reaction to many people, and yet it has nothing on the riots, subversion and protests against the Elizabethan playhouses! As Bob Dylan emerged from the 1950s, America was still dealing with the ‘threat’ of communism and the aftermath of the McCarthy era witch hunts. When he was censored from performing the song on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1963, it fit into a ‘respectable’ surface image of America that still did not accept political satire as appropriate public television entertainment. As Muir so aptly says in the lack of social progress and need for conformity, “You can see 1596 and 1965 as interchangeable.”

Authorship and sources:

As previously mentioned, the concepts of authorship today are very different from the ideas in Shakespeare’s time. Professional dramatists were not considered ‘authors,’ were rarely named on printed manuscripts, and often worked collaboratively. In his chapter on sources, Muir investigates different attitudes to ‘plagiarism’ and attribution - and how traditions accepted that plots, stories, and specific lines were ‘passed around’ and used in a multitude of places. Writers would find a voice and style through imitation - taking previous motifs, melodies, themes and structures, blending them together until something new, individual and relevant emerges. Bob Dylan has always acknowledged this as a tradition he follows. Here, we can begin to see that it is a style Shakespeare also observes.

Muir additionally provides us with a thorough exploration of Dylan’s sources. He does not follow lazy conventional thought, and instead tracks sources back with rigour and illumination. His variety of examples from lyrics and texts provide abundant clarification of his ideas at each step. His analysis of Shakespeare’s sources is equally fascinating, and places into context the modern misconception that writing cannot be original and authentic if it uses quotations and references from other works.

This exploration broadens the work in the earlier chapter on Shakespeare references in Dylan’s work - which is a methodical yet touchingly empathetic cataloguing of quotations, wordings, shared characters, and the power of referencing more than one play or scenario in a single song.

In this chapter, I particularly enjoyed Muir’s analysis of Bob Dylan’s song, ‘Moonlight’ and how the lyrics reference Shakespeare. The rural imagery, that is usually so peaceful and idyllic in Dylan songs, taking a sinister Shakespearean turn, indeed. In a song that always reminds me of the movie thriller ‘The Night of The Hunter’ (1955), the images of death and the crimson clouds - reminiscent of the ‘scarlet billows’ in the Bobby Darin song, ‘Mack The Knife’ (1959) - are menacing and murderous. Following the chapter on Shakespeare in Dylan is the intriguingly titled ‘Dylan in Shakespeare.’ I am reluctant to share any of the examples of this foray because they deserve to be read and discovered through the text, but it was an entertaining sojourn that highlights exactly how cross-cultural references are absolutely relevant and pervasive - how Bob Dylan and Shakespeare can share artistic space, each enhancing and complementing the other, despite the distance in time and genre.

A storm in a teacup:

Arguably the tour de force of the book is the chapter comparing Shakespeare’s The Tempest and Bob Dylan’s album Tempest.

In 2012, with the release of Tempest, there were murmurs all around the Dylan fan circles. After all, The Tempest was Shakespeare’s last play - what if this was Bob Dylan’’s last album of original work? It is what Andrew Muir (in a delicious pun) would call ‘a storm in a teacup.’

Muir points out very clearly that the assumption that The Tempest was Shakespeare’s final work is inaccurate and based upon the conjecture that when the character of Prospero is making a farewell speech at the end of the play - and again referencing the illusion of performance as art - it is the playwright Shakespeare talking to the audience and saying farewell. This is referred to in Dylan & Shakespeare as the ‘straightjacket of biography.’ Looking at The Tempest as a biographical reflection of the writer feeds into the innate human need for audiences to feel closer to the creative people who inspire and influence us. This clouds our view and leads to confirmation bias. As a parallel to Bob Dylan, many fans read autobiographical context into his songs. They value the illusion and mythology because it allows the listener to feel as though they have a deeper connectivity and understanding. It is true that whilst all writers draw on biographical events and emotions, to conflate the real with the fictional is a temptation to be avoided where possible.

The Tempest and Tempest certainly contain many analogous features. They share themes of murder, power, slavery, an upheaval of a world order and, yes, even a shipwreck. Both Dylan and Shakespeare draw heavily on folklore, ballads, mythology and fairy stories. Both Dylan and Shakespeare use classical literature as sources for inspiration.

Reading this particular chapter is absorbing. The depth of analysis, the sharpness of the comparisons, and the sheer amount of detail is staggering.

Conclusion:

Bob Dylan & William Shakespeare: The true performing of it is fully annotated with notes at the end of each chapter, explaining the details of the text and providing a rich resource for any readers wanting to explore even further. A word of warning, though: always listen when Andrew Muir points out which pathways are rich and which are dead ends. I followed a link to an online radio programme that was titled ‘Is Bob Dylan The Shakespeare of Song?’ and yes, Muir was correct in his caveat!

There are interview snippets from Bob Dylan talking about William Shakespeare in a chronologically sequenced section and the book is indexed for quick references. It is structured so it can be used as either a complete text or a reference book to dip into. However, I suggest the first reading would be best tackled cover to cover as some sections enhance and expand on others. And I say ‘first reading’ as I am sure this is the kind of book that will be pulled off the shelf multiple times.

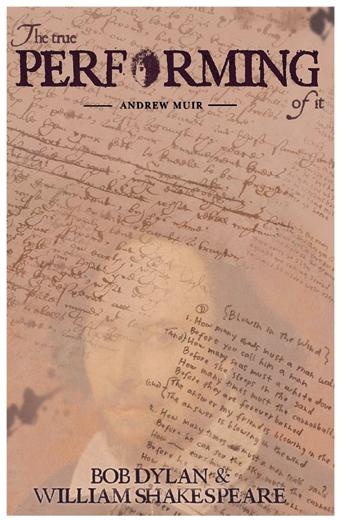

I was deeply disappointed when looking at online links to this book, I noticed that the publisher appears to have altered the cover design in a detrimental way. The original cover is a rich sepia featuring manuscripts and understated pictures of Shakespeare and Dylan. The new version of the cover is gaudy, overly colourful, and childishly simplistic - losing the original cover’s refined maturity. I request that readers don’t judge a book by the garish second cover - the contents remain intact and valuable... and that is what matters at the end of the day.

In closing, it should be noted that the book is a balance between popular interest and academic research. As such, it is not a light read, and is a sophisticated work that would suit those looking for depth, insight and cultural understanding.

If I were to condense this review into three short ‘take-away’ snippets: all art is the perpetual motion of illusion; the performance is everything; and when it comes to understanding both Bob Dylan and William Shakespeare, Andrew Muir knows which way the wind blows.

(c) Tara Zuk 2019

Andrew Muir, The True Performing Of It: Bob Dylan and William Shakespeare

Penryn (UK): Red Planet Books, 2019, paperback, 368 pp., ISBN 978-1-9127-3395-8

Stop the clouds

A review of Barney Hoskyns’ new book, ‘Small Town Talk: Bob Dylan, the Band, Van Morrison, and Friends in the Wild Years of Woodstock’.

Isis

Issue 184

February/March 2016

pages 35-36

‘Small Town Talk’ by Barney Hoskyns is a love story. For Woodstock is not merely a town in upstate New York; here it is a living and breathing character brought to life. It has a personality of its own. It is organic. It grows, matures and changes with the different fashions and eras.

Bob Dylan once told Robert Shelton that Woodstock was ‘the greatest place’ and that “…we could stop the clouds, turn time back and inside out, make the sun turn on and off.”

This is what Hoskyns appears to have achieved in his well-written, detailed and warm biography of a remarkable place. He plays with time, drawing us backwards and forwards in a semi-linear style. The past and the present intertwine. The intriguing life stories and adventures of key players in the history of Woodstock are explored in the same way a tourist might wander off the beaten track on the lower slopes of Overlook Mountain; constantly winding upwards to the pinnacle for the overarching view, but with time to stop and absorb the details of the formative rock structures and the subtle changes in flora and fauna along the journey.

The good, the bad and the eccentric are treated with equal respect and an underlying fondness. Every player in the story has a perspective to be related. Every twist in the tale is driven by motive and opportunity, inspiration and artistry, power and money.

Describing itself in the blurb as, ‘a socio-cultural-musical history of the iconic upstate New York locale of Woodstock,’ Hoskyns’ book is primarily about the story of the Woodstock artistic community in the years following the arrival of Albert and Sally Grossman to Bearsville, but it is much more layered, nuanced and human than the by-line suggests. These are ‘magical times in a magical place’. Culture and history is being formed and influenced.

Artists, artisans, craftsmen, musicians, writers, photographers and poets are amongst those who have been drawn to Woodstock over the years. From the power of Overlook Mountain - with its spectacular views and talk of ancient burial grounds - to the Karma bka' brgyud Tibetan Buddhist community, and the ‘new age’ dabblers who consider Woodstock to be located on a spiritually profound ley line; the creative, the artistic, the unconventional misfits, and the contemplative have all been moved to gather in the neighbourhood.

Contributors to Hoskyns’ book repeatedly talk of mystical creative vibrations, karma, and the sense of peace that people often find in Woodstock - which is precisely the escape and refreshment that the overloaded minds of stressed celebrity artists have been seeking in more recent times, away from the urban spotlight.

And yet, Woodstock is a place of contradictions that Hoskyns is determined to investigate.

In the book’s prologue, following the author’s failed attempts to contact Sally Grossman, and preceding a furtive drive past the ‘No Trespassing’ warnings for a foray along the driveway to catch a glimpse of the Grossman Bearsville property, Artie Traum tells Barney Hoskyns, “There’s a veil of secrecy around all this stuff,” adding, “But one of the whole things Dylan started was ‘Don’t talk to anybody.’”

It is a dissonance that anyone who has lived in a small town may understand. The halcyon outward appearance of tranquility and a close-knit community often conceals an undercurrent of scandal, resentment, old grudges, paranoia, and a desperate attempt by public figures to retain their privacy in an environment where everybody seems to know (or wants to know) everyone else’s business.

The book accurately reflects the contrast between the dark and light. The veneer of a gentle country idyll in the mountains, where people go to seek peace and inspiration, conceals a place with dark and shadowy corners. Drug use, substance abuse, prostitution, fear, distrust, and those gated, high-fenced, properties. Hoskyns mentions, for example, how Bob Dylan became less at ease in Woodstock over time, especially as news of the Charles Manson murders hit the international headlines. Being stalked up those lonely, dark mountain roads by fans willing to hide out in trees overlooking your private space. People invading your property and home, desperate to get some contact with the mysterious idol of the age. The tranquility of Woodstock was transitory. It had become the ‘place of chaos’ Dylan describes in Chronicles.

It is interesting that the generally more politically conservative population of a small and sleepy, somewhat cloistered, bolt-hole, has opened its arms over the years, and embraced the more liberal, bohemian, and outré of newcomers with (mostly) a modicum of grace and harmony -- despite the occasional friction regarding public nudity and alcohol.

Even Bob Dylan fell into that contradictory area between progressive and conservative. Bruce Dorfman recounts to Hoskyns how in 1968, Dylan expressed support for George Wallace, the pro-segregation governor of Alabama who ran for president. As Dorfman puts it, “He was a small-town kid, and a lot of his thinking politically was quite conservative.” How serious was Dylan? Hoskyns adds a wry footnote. During his iconic photo session at Hi Lo Ha, Elliott Landy was told the same thing by Dylan, about supporting Wallace. When Landy later ran into Richard Manuel and asked whether Dylan was on the level, Richard is said to have replied with a chuckle, “I don’t know, you can never tell with Bob if he is serious or not.”

So were these opinions genuine or part of the Woodstock pastime of building an image? Dorfman’s recollections are continued by Hoskyns.

Affectation or not, Dylan took his country-boy act to such an extreme that when he needed a new suit, he asked Dorfman to accompany him to Sears, Roebuck in Kingston. “He had this big truck, and he put Buster in the back,” Dorfman recalls. “At Sears he found a horrendous green suit with saddle-stitched collars and pockets. He thought it was terrific, and I don’t think he was making it up. Innocence gets shattered at some point, but then it comes right back again.” When Dylan showed the suit to Sara -- who in her hippie-maternal way was quite chic -- she smiled. “She said, ‘That’s a lovely suit, Bob,”” says Dorfman. She just tolerated this stuff in a bemused way.

Halcyon days - Sara Lowndes and Bob Dylan pose for a series of photographs by Daniel Kramer. Photograph taken at Vera Yarrow's shack on Broadview Road, Woodstock, March 14th 1965.

And then we see maybe the deepest irony of all: the men who forged the first semblance of the modern day incarnation of Woodstock were overtly anti-semitic. For example, Woodstock was a place where, in the opening years of the twentieth century, Ralph Radcliffe Whitehead had arrived looking for a sanctuary away from the Jewish migration to resorts in the Catskills. He might not have believed that six decades later, his son Peter Whitehead was the person who sold Bob Dylan Hi Lo Ha (without comment on a Whitehead selling Woodstock land and property to a Zimmerman - and it is hoped by Hoskyns that the son had evolved far enough from his father’s ‘ingrained prejudice’ for it not to have mattered or been an issue).

Indeed, it is maybe the most delicious incongruity that the modern phenomenon of the near mythical status of Woodstock in today’s culture, language and music, was brought about primarily by the power, influence, and vision of two Jewish men.

Albert Grossman and Bob Dylan.

Janis Joplin (right) embraces her manager, Albert Grossman, at the press party for her signing with CBS, February 1968, New York City. Photograph by Elliott Landy.

There are countless others who have played significant roles in establishing and maintaining the reputation of the Woodstock area. The book is full to the brim with their stories, anecdotes and recollections - either from personal reminiscence, or through gathered writings and interviews.

And yet, Grossman and Dylan are the two pillars, the walls and roof of this modern history of Woodstock.

Hoskyns provides ample detail about Albert Grossman’s fascinating biography and influence. There are plenty of stories, anecdotes and facts to inform and entertain those interested in the background of Bob Dylan’s connection to Woodstock. In fact, Grossman and Dylan weave through every section of the book in one way or another. Sometimes solid entities with active roles, sometimes no more than smoke and mist curling around the legs of the players and silently pushing them forward.

Janis Joplin, The Band, a lovely insight into Levon Helm’s later years before his passing, Van Morrison, Todd Rundgren, Paul Butterfield, Jimi Hendrix… far too many iconic performers and celebrities are included in the book to be listed here. They explode into the narrative and then are gone, with their stories all interconnected.

And, of course, some pages are dedicated to that elephant in the room - the Woodstock music and arts festival, that “Aquarian Exposition: 3 Days of Peace & Music” which took place in August 1969. The book shows how Woodstock and ‘The Woodstock Festival’ are not synonymous in either spirit or in location (the festival being held 69 kilometres southwest of Woodstock, near White Lake, Bethel). In fact, for many people ‘The Woodstock Festival’ irreparably and negatively changed the town of Woodstock. Many shared Bob Dylan’s distaste for the idea, and it was unsurprising when Dylan himself opted to perform at the Isle of Wight festival in the UK in the summer of 1969, rather than attend the festivities in Bethel.

‘Small Town Talk’ includes 16 pages of black and white photographs that are unfortunately rather small and not always as clearly reproduced as one would like. However they do serve to illustrate much of the important historical content of the book.

With a solid bibliography, thorough notes on quotations and sources, and even a small playlist suggestion that takes any readers unfamiliar with the performers in the book on a musical tour of Woodstock from 1968 - 2010, this book is informative, entertaining and eminently readable.

Certainly, ‘Small Town Talk’ has neatly caught the significance, the atmosphere, the characters, and the social history of Woodstock. Although it is geared for the more general cultural and musical history enthusiast, and much of the information is covered in other books, this is a fine addition to the library of anyone interested in the music of Bob Dylan. It includes the stories of some of the people surrounding Dylan and working with him during the 1960s and early 1970s, with openness and touches of humour, offering more in content and approach than a standard celebrity biography.

‘Small Town Talk’ by Barney Hoskyns (hardcover, 380 pages) is due to be released through Da Capo Press, March 15th 2016.

Hoskyns, Barney. Small Town Talk: Bob Dylan, the Band, Van Morrison, and Friends in the Wild Years of Woodstock. Boston : Da Capo, 2016. 9780306823206

(c) Tara Zuk, 2016

All Rights Reserved